What Nobody Tells You About Following Your Passion

As the year ends, I’m getting reflective. Specifically, about the gap between the dream and the doing.

I moved to Sweden to pursue a master’s in strategic entrepreneurship. On paper: perfect. In reality: I’m working 20 hours a week as a Sales Manager for a German company while trying to build my own venture through the program.

Ever since I found The Lean Startup by accident in our university library, I’ve been obsessed with entrepreneurship. Maybe because I’ve always rejected traditional paths. My brain naturally asks: “What if we ignored how it’s always been done?” Moving to Sweden was part of that, another escape from systems that never fit, like the German school system.

Three months in, here’s what’s actually happening:

The work reveals what you’re avoiding.

Sales goes against everything in my personality. Twenty hours a week of pushing, performing, persuading. It feels completely wrong.

But that wrongness is teaching me something. When you spend time doing what’s false, you recognize what’s true. The discomfort isn’t the obstacle, it’s the contrast that makes my real work visible. Maybe the job isn’t in the way. Maybe it’s the sandpaper.

Academia might not be the answer.

Thirty-five master’s students in my cohort. Not one inspiring conversation.

At first, I blamed myself, maybe I’m not trying hard enough, maybe I’m too judgmental. Now I think: maybe I’m in the wrong room, and that’s information, not failure.

Before this, I worked in Berlin’s startup scene, surrounded by people with more experience, different perspectives, actual scar tissue. They stretched me. Here, everyone knows as little as I do. We’re all equally inexperienced.

The education I’m getting isn’t from the curriculum. It’s from the gap between what they’re teaching and what I already know to be true. That gap is where my actual work lives.

Boredom is where the signal emerges.

Moving to an 80,000-person town in the middle of Sweden gave me something Berlin never could: the absence of everything else.

No warehouse raves. No FOMO about tonight’s event. No constant stimulation disguised as opportunity.

What’s left is uncomfortable at first. Then it becomes clarity.

I started meditating because my head felt like chaos I couldn’t control. Now it’s my favorite practice, not because it solves anything, but because it creates space for things to settle. The mud has to settle before you can see through the water.

Flow is a compass, not a destination.

Ninety percent of my day is forcing myself to do hard things: sales calls on a schedule, assignments I don’t care about, other people’s priorities. Time crawls.

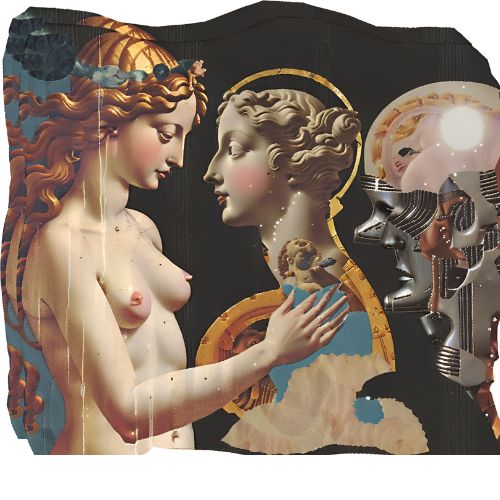

But when I work on what actually interests me, this writing, the book I’m building, art work, time disappears. I’m not watching the clock. I’m in it.

I’ve learned to trust that disappearance. Flow isn’t just a pleasant state, it’s directional for me. It points toward what’s real for you.

My brain doesn’t work linearly, so I stopped forcing it to.

I keep 2-3 projects open at once: this blog, a book, Adobe. When I’m stuck on one, another one calls to me. I used to fight this, thought it was distraction, lack of discipline.

Now I follow it. The mind knows what it needs. When I’m focused on one thing, my brain works on the others in the background. Suddenly an idea arrives, and I switch. The flow continues.

Csikszentmihalyi said flow happens at the edge of challenge and skill. But there’s another element: timing. The work knows when it’s ready. Following that timing isn’t distraction, it’s listening.

The gap between expectation and reality is where you find your actual path.

I came here expecting peers, inspiration, the perfect environment to build something meaningful.

What I’m actually getting: isolation, doubt, friction, the daily grind of managing two competing demands.

But here’s what I’m learning: the romantic version of following your passion and the real version are completely different.

One is inspiration and flow and meaning. The other is discipline and sacrifice and showing up when you don’t feel like it.

Most people quit when they hit that gap. They assume they chose wrong.

I’m starting to think the gap is the path. What you thought you should want versus what you actually want, that tension is where your real work reveals itself.

So what now?

I’m not sure yet. But I’m learning to trust the discomfort more than the comfort. To protect my attention like it’s sacred. To let some balls drop and see which ones I actually chase.

The program will end. The job will change. Sweden might not be forever.

But the question underneath all of it Am I moving toward my own voice or away from it? that’s the only one that matters.